In light of Rare Disease Day on February 28th and the upcoming World Lymphedema Day on March 6th, I thought it’d be the perfect time to do an overview of the rarer categorization of lymphedema: primary (also known as hereditary) lymphedema. Now, I’m not a medical professional, so this is by no means intended to be a comprehensive overview — think of it instead as a primer on primary!

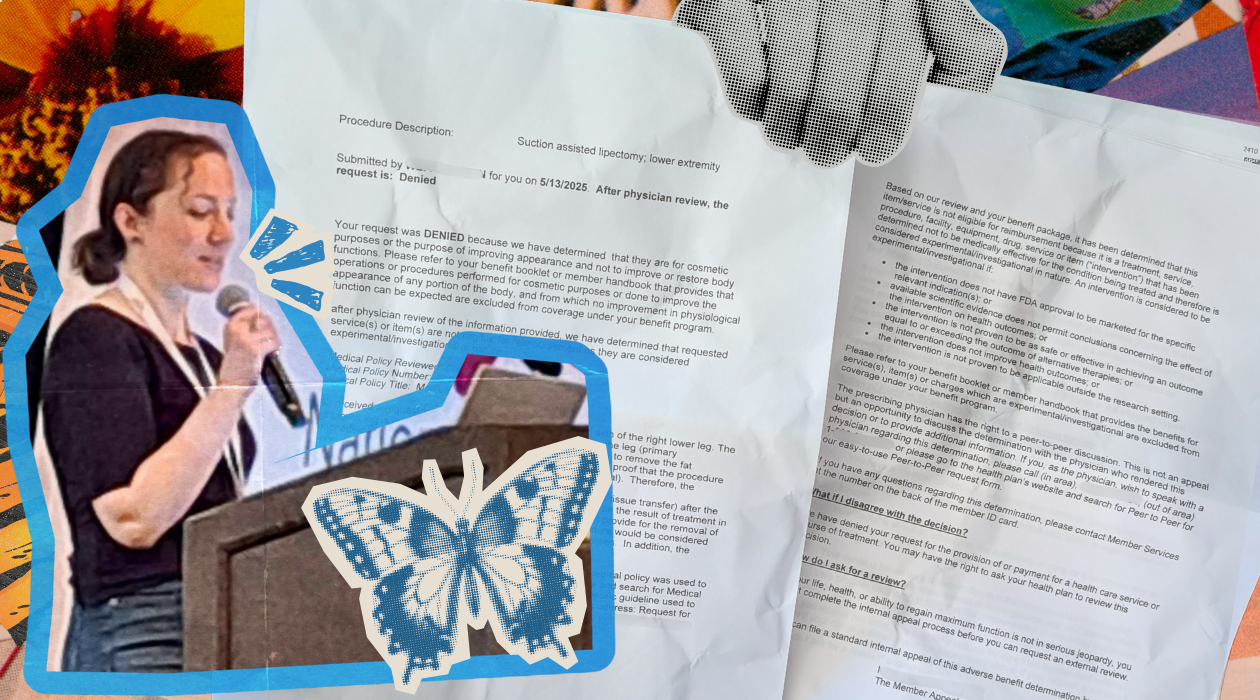

Primary lymphedema is close to my heart — or, rather, my leg — as I’ve been living with primary since infancy. My parents, concerned about my “puffy foot,” took me to different specialists and doctors throughout my childhood, but no one had any answers. At least, none of the right ones: one pediatrician suggested I’d “grow out of it”; another recommended I wear an arch support. None suggested lymphedema.

These medical professionals saw the swelling and acknowledged there was something going on, but they didn’t say lymphedema — they couldn’t, because they weren’t aware of it. They didn’t know that word.

Unfortunately, that lack of awareness led to my living fourteen years without a diagnosis, and even longer without treatment. To finally receive a diagnosis and a name for my “puffy foot” was overwhelming and scary, but ultimately really empowering.

Primary lymphedema

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), primary (or hereditary) lymphedema is a genetic developmental disorder affecting the lymphatic system. It’s an inherited condition that’s more or less “decided” genetically before birth, although symptoms aren’t often visible until later in life.

Quick review on the lymphatic system: the lymphatic system is a circulatory network of vessels and ducts that move protein-rich lymph fluid throughout the body, filtering it through lymph nodes to remove cellular debris and toxins before returning it to the bloodstream.

Primary lymphedema occurs when there’s obstruction, malformation, or underdevelopment of the lymphatic vessels. When this happens, the lymphatic fluid doesn’t move or drain like it should; instead, it collects in the soft layers of subcutaneous tissues under the skin and causes swelling to develop.

![By OpenStax College [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/thelymphielife.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2201_anatomy_of_the_lymphatic_system.jpg?resize=950%2C1006&ssl=1)

Classifications

Primary lymphedema is estimated to affect 1 in 6,000 people within the general population, and is classified by age of onset:

- Congenital hereditary lymphedema. Congenital means the swelling is present at birth if not shortly after, during early infancy. Often referred to as Milroy’s disease, congenital lymphedema is the rarest type of primary lymphedema. The exact prevalence is unknown, but approximately 200 cases have been reported in medical literature.

- Lymphedema praecox. Also known as Meige disease, lymphedema praecox develops around puberty. Accounting for approximately 80% of cases, lymphedema praecox is the most common type of primary lymphedema.

- Lymphedema tarda. If lymphedema develops after the age of 35, it’s diagnosed as lymphedema tarda.

Primary lymphedema affects females more often than males, and is most common in the legs, but it can also develop in the arms, trunk, face, or genitals. The symptoms of primary lymphedema are similar to secondary and can include feelings of tightness and discomfort in the affected area, tingling sensations, and changes in skin texture or thickness along with the requisite edema.

Preventing Infection and Managing Symptoms

Since the lymphatic system is compromised, all this protein-rich lymph fluid is stagnant, saturating the body’s tissues; this makes people with lymphedema especially prone to infections, the two most common being cellulitis (a bacterial infection of the skin and underlying tissue) and lymphangitis (an infection of the lymphatic vessels).

Know the signs of infection! If your skin is warm to the touch – if it’s red or has red “skin streaks” present – if there’s more swelling than normal – if you’re experiencing fever, chills, or headaches – get to the doctor! If left untreated, these infections can run haywire and develop serious complications, such as septicemia, skin abscesses, ulcerations, or tissue damage. Good skin care is important here, as keeping the skin moisturized makes it less likely to crack or break (which is an invitation for bacteria!).

Consistent treatment is key to preventing infection, keeping the swelling under control, and maintaining quality of life. I go more in depth on lymphedema treatment methods and therapies in a previous post, but it mostly comes down to graduated compression (either through well-fitting garments or multi-layered bandaging) and a specialized massage technique called manual lymph drainage to promote lymphatic flow. Additionally, regular exercise, a healthy diet, and good skin care are helpful habits to support lymphedema symptom management!

Genetics

The National Organization for Rare Disorders explains the genetics behind primary lymphedema as follows:

Many researchers believe that hereditary lymphedema may result from changes (mutations) in one of the different disease genes (genetic heterogeneity). Most cases of hereditary lymphedema type IA and type II are inherited as autosomal dominant traits. Genetic diseases are determined by the combination of genes for a particular trait that are on the chromosomes received from the father and the mother. Dominant genetic disorders occur when only a single copy of an abnormal gene is necessary for the appearance of the disease. The abnormal gene can be inherited from either parent, or can be the result of a new mutation (gene change) in the affected individual. The risk of passing the abnormal gene from affected parent to offspring is 50 percent for each pregnancy regardless of the sex of the resulting child.

Investigators have determined that some cases of hereditary lymphedema type IA (Milroy’s disease) occur because of mutation in the FLT4 gene which encodes of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) gene located on the long arm (q) on chromosome 5 (5q35.3). Chromosomes, which are present in the nucleus of human cells, carry the genetic information for each individual. Human body cells normally have 46 chromosomes. Pairs of human chromosomes are numbered from 1 through 22 and the sex chromosomes are designated X and Y. Males have one X and one Y chromosome and females have two X chromosomes. Each chromosome has a short arm designated “p” and a long arm designated “q”. Chromosomes are further sub-divided into many bands that are numbered. For example, “chromosome 5q35.3” refers to band 35.3 on the long arm of chromosome 5. The numbered bands specify the location of the thousands of genes that are present on each chromosome.

Investigators have determined that some cases of hereditary lymphedema type II (Meige disease) occur because of mutations of the ‘forkhead’ family transcription factor (FOXC2) gene located on the long arm (q) of chromosome 16 (16q24.3).

If that was confusing, don’t worry — that was a ton of medical jargon! To put it simply, there’s a lot of genes involved in lymphatic development, and a mutation or change in any one of these can theoretically cause primary lymphedema. When a bunch of different genes have the potential to cause the same condition like that, it’s called genetic heterogeneity.

Primary lymphedema is an autosomal dominant disease, which means a person has a 50/50 chance of inheriting the mutated lymphedema-causing gene from a parent with primary lymphedema. The parent carrying the mutated gene may not visibly have primary lymphedema, however, as the gene has incomplete penetrance: the genetic mutation can be inherited but not expressed. In other words, it skips a generation.

The gene also has variable expression, which means it varies in the way it’s expressed from person to person. So, if your mother has primary lymphedema in her right leg and you inherit the lymphedema-causing gene, you may have it express as swelling in your left arm; or, it could be bilateral in your legs. Or, you may have it your right leg, just like mom. It — well, it varies!

The lymphatic system is incredibly complex and there’s still a lot of unknowns surrounding its development, but research into the genetic mechanisms behind primary lymphedema can provide valuable insight into the development and function of the lymphatic system itself. This sort of understanding not only benefits the development of new and improved treatments, but could also help identify the genetic risk factors that make someone susceptible to developing secondary lymphedema, too.

The Importance of “Lymphatic Self-Awareness”

I’m 26 years old now, but what happened to me is still happening to countless others living with primary lymphedema: bouncing from specialist to specialist only to be misdiagnosed and untreated; living without answers, without proper treatment, without even a name to call the disease. For us primary lymphies, this is especially urgent, as we often lack the resources and support that many secondary lymphies have access to via cancer services or dedicated research studies (and even those are sometimes not enough!).

One way to combat this lack of awareness is for us as patients to become knowledgeable about lymphedema itself. Knowledge is power after all, and our “lymphatic self-awareness” can help inspire us to take action, be it on a personal level by becoming more consistent with our treatment or asking our doctors more questions; or on a larger scale by starting more conversations about lymphedema, or actively advocating on behalf of improved treatment and funding for lymphatic research.

I feel like I say this in practically every post, but: we are our own best advocates. It starts with us, so we’re doing ourselves and our global lymphedema community a service when we’re well-informed ambassadors of lymphedema!